Processing the Dark Cloud: SEL in the Time of Covid-19

By Aneesa Sen

26 June 2020

The stay-at-home orders issued in Massachusetts, where I teach, on 13 March 2020, caused an abrupt—if not unexpected—cessation of normal life. My sixth-grade class was deeply affected and we left school with an underlying sense of dread. While we prepared for remote teaching, we had very little idea how it would actually work. Additionally, understanding (and supporting) the reasons behind the shutdown did not lessen my students’ or my own anxiety about what would happen next. I knew it would be imperative to tackle the social-emotional impact of the shutdown before attempting to move too far forward with the curriculum.

Finding Resources for Teaching During Covid-19

Fortuitously, a colleague directed me to explore K-12 resources for educators offered by the REACH initiative at Harvard Graduate School of Education, where I found some great books centered on the experience of children traversing the pathways of loss and grief.

At first, I was hesitant to use online resources that were clearly aimed at children in extreme conflict situations. Upon reflection, however, I realized that being apart from teachers and classmates was a traumatic experience for my students and had some parallels to the experience of refugee children. The sense of loss my students were experiencing, coupled with their fear for parents’ and grandparents’ health, meant that my students really did need REACH’s materials.

Using Metaphors: Recognizing the Dark Cloud Around Us

I chose to work with Bigger, Stronger, Braver created by Winki Chan and Natasha Raisch, even though it is geared towards younger children, because the authors use the recurrent metaphor of a dark cloud—a metaphor I thought would be ideal for processing emotion around Covid-19 and its consequences. The children’s book details the experiences of a young Colombian boy named Darío. He has many happy moments in his life, but there is a dark cloud that periodically threatens his village and its inhabitants. In the end, Darío works with other children to successfully defeat this cloud. This is a powerful ending, one whose utility cannot be overestimated. Children need to feel that they have agency, particularly in difficult times. Bigger, Stronger, Braver clearly and simply magnifies this message.

Teaching Plans for Bigger, Stronger, Braver

My students and I started working with this book in the third week of our distance learning program. Prior to the third week, all teaching had been asynchronous. This was the first text I used when we started synchronous learning. The book worked well as a read-aloud, even on Zoom. I shared my screen so that students could see the pictures and participate in the reading. We looked closely at the gorgeous illustrations, and we spoke about the dark cloud in our lives. Students were able to articulate what fears and worries lived in their own dark clouds.

After reading, I assigned the guiding questions included in the book to my students as discussion questions. The questions allow assessment of comprehension on multiple levels, starting with simple questions to those requiring more complex synthesizing and extrapolation.

We read the questions together and then I split the students into small groups and put them in breakout rooms for about five minutes per question. We came back together after each short breakout so students could share their observations with the whole class. We went through all the questions in this way, always coming back as a class to discuss observations and extrapolations. By the end, students were making connections between Darío’s experience with the dark cloud and their own with the time of Covid-19.

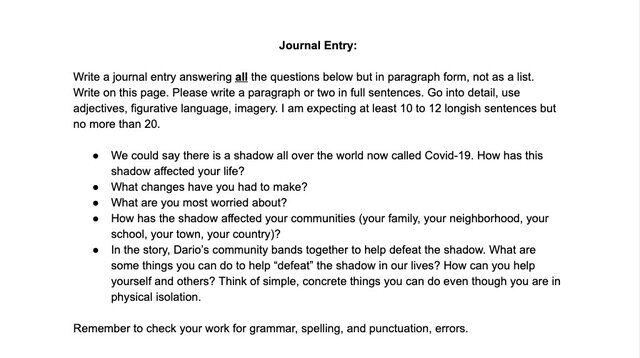

The final independent assignment was to write a guided journal entry detailing students’ own lived experiences. They took full advantage of the opportunity to write freely without the usual constraints of an expository assignment. Their responses ranged from mourning the loss of in-person connections, to deep concern for the health of grandparents, to calls for action. All responses included at least a small element of awareness that they had some control over what happened next.

In the end, I found this text, and the thoughtful questions, to be exactly right for our current situation. My students appreciated the simplicity of the text and responded to the complexity of emotion underlying the story. Perhaps, most importantly, they were able to identify with the message of empowerment.

Disclaimer: The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this publication belong solely to the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of REACH or the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

About the author

Aneesa Sen is a sixth-grade Humanities teacher at Shady Hill School in Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA. Her work with middle schoolers focuses on the intersectionality of identity and foregrounds social-emotional learning as the foundation for all other types of learning. She is active in the LGBTQ+ rights movement and mentors/guides LGBTQ+ youth.

Connect with Aneesa on LinkedIn.

You might also like

K-12 resource | Bigger, Stronger, Braver

Insight | Continuing learning and community during school closures: Lessons from our work at REACH

HGSE article | Making space for difficult discussions