‘My Teachers Didn’t Notice’: Nurturing the Well-being of Internally Displaced Children through Trauma-informed Education

By Nomisha Kurian

02 October 2020

Child laborer Jamlo Makdam was only twelve when fatigue and dehydration caused her to collapse. She had been walking for approximately 93 miles for three days, attempting to reach her home village. Although she did not know it, she was only an hour away from home when she died.

Jamlo was one of millions of children swept up in a wave of internal displacement after India’s nationwide lockdown on March 24th, 2020. With the sudden loss of essential services such as public transport, migrant workers and their families were left stranded. Deprived of their livelihoods overnight, they used their dwindling supplies of food and savings to try and return home on foot. Children were forced to walk as many as 621 miles—both child migrant laborers like Jamlo, and the offsprings of adult migrant workers.

It is too late to advocate for Jamlo’s well-being. However, might we honor her life—and the tragedy of its loss—by prioritizing the well-being of displaced children in educational policy and practice?

Understanding children’s struggles and histories: trauma-informed education

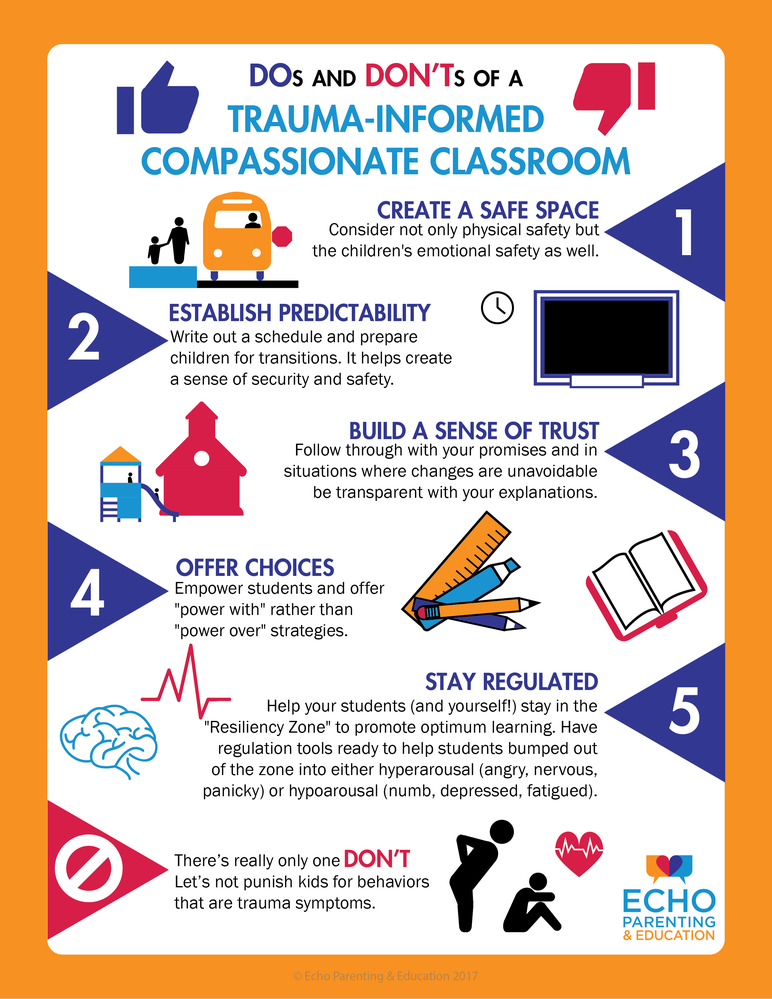

My research examines trauma-informed education, a movement that has attracted much interest from policymakers, researchers, and educators in recent years. Trauma-informed care endeavors to respond to the adversities children face, and to shape whole-school policies and pedagogies around a deeply contextualized understanding of child well-being. In its blending of psycho-social and socio-cultural factors, it examines the multiple ecologies within which children live and learn. While schools have limited capacities to tackle all the adversities children face in their broader economic, social, and geo-political context, it seems worth investing material and relational resources into helping each learner feel safe, seen, and heard.

From February to March, I conducted two months of fieldwork with 11-13 year olds living in poverty in Mumbai. Although this fieldwork took place before the lockdown, some children had already experienced forced displacement before Covid-19, due to their socio-economic vulnerability; they had been living on the street and seen their shanties (huts) destroyed in a demolition drive. Their narratives yield insights into the possibilities of trauma-informed education in response to child displacement.

‘I don’t think anybody cared’: Helping children feel seen and heard

My child-participants’ well-being appeared significantly affected by their schools’ levels of sensitivity to their struggles. For example, eleven-year-old Rani lost her home in a demolition drive and experienced several types of trauma simultaneously: watching her home of 10 years be destroyed by a bulldozer in the middle of the night, dropping out of school due to financial strain, and leaving behind all her kinship and peer networks in her old neighborhood (“All my cousins, my friends, my aunties, my uncles, all gone”).

When she rejoined school, she did not find much support or solace:

“I didn’t go to school for some time. My teachers didn’t notice. I don’t think anybody cared. I didn’t tell anyone. Nobody asked about me...when I came back, I could not pay attention in lessons. I just stayed alone. I don’t think anybody noticed anything had happened to me.”

Rani named this sense of invisibility one of the “things that made me most sad.”

Rani’s response bears out findings from trauma-informed education about the importance of supportive teacher-child relationships and peer networks in settings of adversity (Walkley & Cox, 2013). What appears to scaffold impactful caring relationships is a deep understanding of the roots, workings, and consequences of adversity in children’s lives. For children returning to school after internal displacement, schools must therefore be mindful of manifold stressors.

Children from migrant worker backgrounds were already suffering multiple forms of deprivation pre-pandemic, including little access to clean drinking water, low sanitation facilities and financial insecurity (Nayar, 2020). Now, the pandemic has imposed new forms of strain. A survey conducted in May by the Stranded Workers Action Network shows that, without access to salaries or cash relief, 78% of 9,981 workers had only Rs. 300 or less (3 GBP) in their pockets. Food distress was acute: out of 10,170 workers, 72% reported having rations for less than 2 days. The trickle-down effects of these deprivations on children (from malnutrition to anxiety) needs to be recognized in a trauma-informed educational response.

The embodied and psychological toll of migrants’ journeys also needs to be noted. With railway, bus, and auto rickshaw services suspended, the tens of thousands of children journeying on foot ranged from ten-month-old toddlers going without food to older children contemplating dropping out of school because of their newfound destitution (Pandey, 2020). Multiple threats to child well-being included exhaustion, heatstroke, hunger, bereavement, and grief due to losing their caregivers to fatigue or starvation (Nayar, 2020).

A whole-school ecology of care

Had Jamlo been able to live, and had Rani been able to access a supportive school environment, trauma-informed care might have entailed a relational, inclusive, and whole-system response to the stressors they faced. For child-victims of internal displacement, this could mean socio-emotional support (empathetic teacher-child relationships, home-school partnerships, peer support, counseling); structural and material support (free school meals, fee concessions); and academic flexibility (pedagogies adjusted to the embodied and cognitive effects of trauma upon learning).

Building on children’s pre-existing strengths, capabilities, and relationships within an asset-centered approach has been recommended, rather than viewing learners in a deficit light (Brunzel, Water, & Stokes, 2015). As a pioneer of trauma-informed approaches puts it, seeking to harness ‘the healing power of community’ reinforces that ‘we are a hopeful species’ and that ‘working with trauma is as much about remembering how we survived as it is about what is broken’ (van der Kolk, 2015, p. 244).

Disclaimer: The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this publication belong solely to the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of REACH or the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

References

Adhikari, A., Narayanan, R., Dhorajiwala, S., & Mundoli, S. (2020). 21 days and counting: Covid-19 lockdown, migrant workers, and the inadequacy of welfare measures in India. Stranded Workers Action Network. https://www.thehindu.com/news/resources/article31442220.ece/binary/Lockdown-and-Distress_Report-by-Stranded-Workers-Action-Network.pdf

Brunzell, Tom, Waters, Lea, & Stokes, Helen. (2015). Teaching with strengths in trauma-affected students: A new approach to healing and growth in the classroom. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(1), 3-9. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000048

Chauhan, A. (2020, May 15). Uttar Pradesh: Kid sleeps on bag that his mother pulled. Times of India. Retrieved from http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/75746164.cms

Nayar, P. K. (2020). The long walk: Migrant workers and extreme mobility in the age of corona. Journal of Extreme Anthropology, 4(2), E1-E6. https://doi.org/10.5617/jea.7856

Pandey, V. (2020, May 19). Coronavirus lockdown: The Indian migrants dying to get home. BBC News. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-52672764

Roberton, T., Carter, E. D., Chou, V. B., Stegmuller, A. R., Jackson, B. D., Tam, Y., Sawadogo-Lewis, T. & Walker, N. (2020). Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: A modelling study. The Lancet Global Health, 8(7), E901-E908. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30229-1

Van der Kolk, B. (2015). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York, New York: Penguin Books.

Walkley, M, & Cox, T. L. (2013). Building Trauma-Informed Schools and Communities. Children & Schools, 35(2), 123-126. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdt007

About the Author

Nomisha is a PhD candidate at the University of Cambridge and a former Henry Fellow at Yale University. Her interest in building safer, more inclusive schools has led her to explore issues such as: How might human rights law support bullied and socially marginalized young people? How might teachers safeguard children in high-crisis settings and address threats such as domestic violence and child labor? How might empathy be taught in lessons about global poverty? Can citizenship education build peace? Her work has been published in the Palgrave Handbook of Citizenship and Education, the Journal of Peace Education, the International Journal of Human Rights, and the International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning.

You can read Nomisha’s work here and follow her on Twitter @nomishakurian.