Crisis within a Crisis: Education of Refugees during School Closures in Lebanon

By Dagan Rossini

06 April 2020

For Suha Tutunji, providing education for individuals affected by conflict is what she and her team do best. During her time as academic director of Jusoor, an NGO serving Syrian refugee children in Lebanon, Tutunji has tackled education emergencies head on and found innovative ways to ensure her students stay engaged and supported.

As the Covid-19 pandemic sweeps across the world, putting roughly 9 out of 10 schoolchildren worldwide out of school and testing Jusoor’s own operations, Tutunji and her team did not sit idle waiting for the virus’s arrival—they actively prepared for it.

“A school is a school—it should remain running, no matter what.”

In a recent conversation with REACH director and founder Sarah Dryden-Peterson, Tutunji talked about her team’s planning for Covid-19, as well as some lessons learned from previous experiences, both personal and professional, on how best to address this ‘crisis within a crisis.’

Like many other organizations working in refugee settings, Covid-19 has forced Jusoor to grapple with a public health concern—which cuts across refugee and national status—within the larger refugee crisis, exacerbated further by the socio-political situation in Lebanon.

Covid-19 has forced Jusoor to rethink its entire delivery of education; yet even this global pandemic has not stopped her organization from helping Syrian children access better opportunities. “A school is a school—it should remain running, no matter what,” says Tutunji.

Planning for disruptions

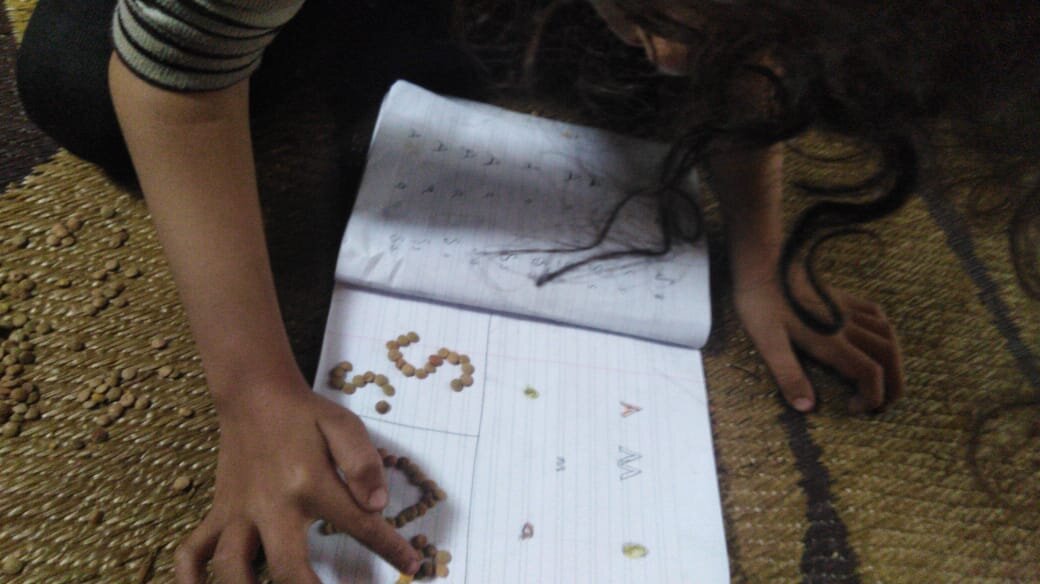

Anticipating Lebanon’s school closures, Tutunji held a meeting with her teachers and IT staff several weeks ago to brainstorm ideas. “We foresaw Covid-19 in China, Italy, and Spain, so we knew we were going to get it.” Given the prevalence of mobile phones, she and her team decided to harness the power of WhatsApp to send updates and tasks to students through voice messages and take pictures of the work that they have been doing in class.

Attention to inequalities

Printed materials were floated as one possibility but, based on her own experience as a student during Lebanon’s civil war, Tutunji knew this would not be productive for her students’ learning. According to her, 92 percent of students’ family members at home are illiterate, so relying on someone else to read and review printed packets would only hurt rather than help their education. Familiar technology such as WhatsApp does not force students to depend on their parents. Instead, Tutunji explained, “They can do it on their own and enjoy it”.

“We’re basing the lessons on what the children have already learned,” Tutunji explained. Rather than overcoming the difficulty of learning new topics online, teachers agreed to focus on lessons and subjects covered in the past five months, which students can review in order to solidify knowledge and skills. Once classes resume will they jump straight into new topics. This strategy is meant to promote equitable learning amongst all pupils, rather than exacerbate learning gaps.

Ensuring emotional support

Based on her past experiences with emergency education, Tutunji knows that there is much to worry about regarding the emotional implications of such traumatic events on children. Jusoor counselors are sending tips to parents via WhatsApp about how to support their children during this time. The return to physical school will require more circle time focusing on students’ emotions and working with a psychologist, as well as parents and teachers as partners. It will also require a restructuring of the curriculum and additional activities that help children to catch up on what they have missed, but not miss out on opportunities to play. “You do (with) what you have to make change. You have to be flexible.”

Sense of purpose to work together

Yet Tutunji is hopeful: Even before this ‘crisis within a crisis’, there was already a shared sense of purpose and understanding among teachers to work together during difficult times. Many who work for Jusoor are from Syria, as are their students, and therefore familiar with their contexts. Despite their own experiences of conflict, Covid-19 has brought the teaching staff closer. It has encouraged them, Tutunji said, to “put on another hat and give from their hearts.”

It is this spirit of resilience and unity, exhibited during past emergencies, that brought everyone together to devise a new education plan. And it is this same spirit that will allow Jusoor to continue providing refugee students with a quality education, and hopefully weather yet another passing storm.

Disclaimer: The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this publication belong solely to the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of REACH or the Harvard Graduate School of Education.