Political Economy of Refugees: How responsibility shapes the politics of education

A Theory for the Political Economy of Refugee Education

by Shelby Carvalho and Sarah Dryden-Peterson

World Development 173(2024)

In a new article published in World Development, we propose a theory for understanding the political economy of refugees in low- and middle-income countries. Situating our theory in the education sector, we illustrate the ways that features of political environments – including actors, demand, and incentives – interact with national systems to shape the education opportunities available to refugees. We consider the ways traditional theories related to the political economy of education for citizens vary when applied to refugees under the increasingly common model of ‘responsibility sharing,’ in which service provision is meant to be shared between host country governments and global actors.

Drawing on prominent theories from political science, economics, sociology, education, and refugee studies, as well as many years of research, policy, and practice experience, we suggest that the political economy of refugees can be understood as distinct from that of citizens. We argue that this is because engaging with the political economy for refugees requires different considerations related to responsibility for service provision and requires reexamining traditional assumptions about possible futures and time horizons.

The political economy of education

The political economy of education can be understood as the ways in which economic interests and political institutions interact to shape education goals, systems, curriculums, and learning outcomes. The role of the state and its interest groups are central to understanding political economy in this way. The political economy of education is shaped by demand for education, ideas about the purposes of education, incentives, and perceptions and frameworks for responsibility.

Around the world, governments have the primary responsibility for providing education to citizens and have social and economic incentives to do so. However, these incentives - often driven by goals of economic returns, nation building, and vocationally-oriented socialization - rely on some degree of certainty that the citizens being invested in will be part of the state over the long-run.

Unique political economy features of education for refugees

Responsibility

While governments vary in the extent to which they sufficiently deliver education to citizens as well as in the degree to which they outsource to non-state providers, the fundamental responsibility for providing education is understood as lying squarely with governments. For refugee education, formal lines of responsibility typically extend outside of the host country to include global actors and others external to the host government. In practice, lines of responsibility, particularly under responsibility sharing models, remain opaque. In our theory, this ambiguous and often contested responsibility is a defining feature of the political economy of refugee education. We argue that it interacts with possible futures for refugees in a host country and has implications for how the purposes of education are understood, the nature of demand for and actors involved in the provision of education, as well as in defining the incentives influencing preferences and decisions related to refugee education.

Time horizons and perceptions of refugee futures

Education is inherently a future-oriented endeavor. In contrast to citizens, refugee futures in a host country are highly uncertain. Refugees may not be allowed to stay in the host country over the long-term, may not have access to necessary productive opportunities like employment or rights like citizenship, or may not wish to remain in a particular country. This uncertainty challenges assumptions about time horizons and potential returns that host governments can expect to realize from investing in mass education.

Purposes, actors, demand, and incentives

Unclear lines of responsibility coupled with uncertain or impossible futures in a host country raise critical questions about the purposes of education for refugees (why education?), the actors involved and nature of demand (who is involved and what do they want?), and incentives (why are these things wanted?).

In traditional theories of the political economy of education, governments and their interest groups play a central role in defining each of these features. For refugee education, traditional actors, like teachers or local politicians, may have different preferences for refugees than for national students, or may be uninterested in refugee inclusion. At the same time, new actors or those who typically play less prominent roles in domestic education systems, like UNHCR or other global and non-state actors, may become more involved, thus changing the nature and dynamics of incentives related to service provision.

The theory

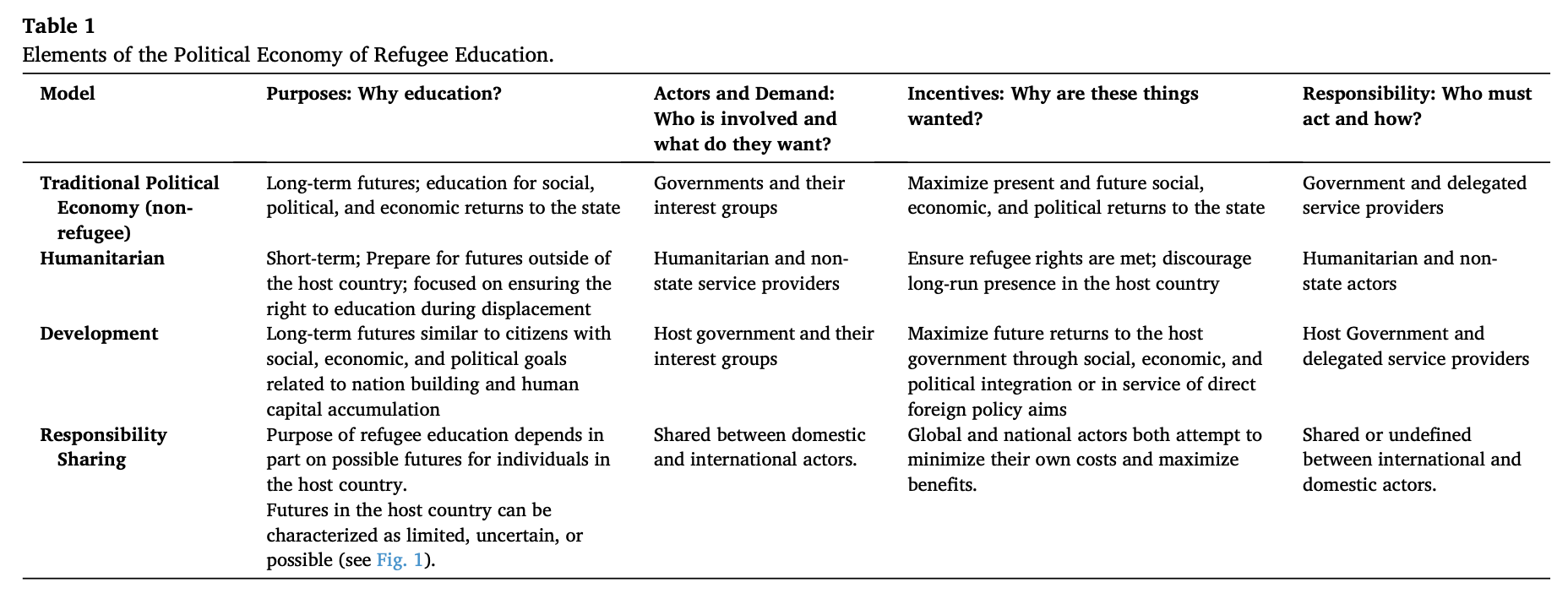

Bringing together traditional elements of the political economy of education, we hypothesize conditions under which we expect to observe variation when applied to different models of refugee education, the key features of which we summarize in Table 1.

See Carvalho & Dryden-Peterson, 2024, p.4

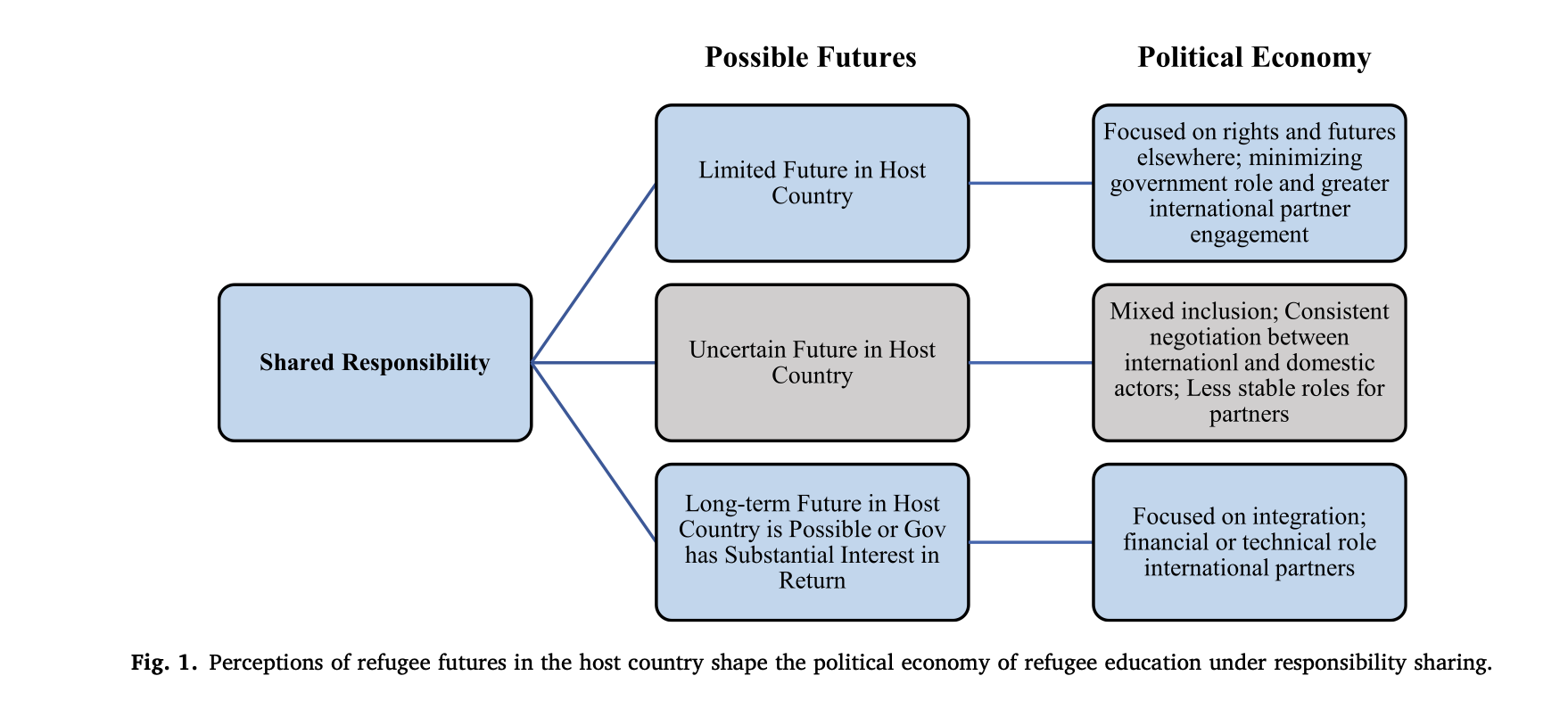

We hypothesize that the scope and boundaries of possible futures for refugees in a host country will have implications for if and how responsibility is shared across domestic and global actors, influencing political economy considerations (Figure 1).

See Carvalho & Dryden-Peterson, 2024, p.4

In countries where refugees have few future opportunities in their host country (limited futures), we expect political economy considerations to resemble those associated with humanitarian models of service delivery in which host government responsibility remains minimal and the purpose of education is to prepare refugees for futures elsewhere.

When refugee futures in a host country are possible but uncertain due to limited legal protections or precarious political environments, we expect to see mixed inclusion and consistent (re)negotiations between host government and global actors.

Finally, when refugees have possible futures in a host country through employment or citizenship pathways, we expect political economy considerations to more closely resemble traditional political economy models for citizens.

Practical implications

As host governments and the global community grapple with decisions about and responsibility for protection of refugees’ rights and service provision, it is critical to understand the ways in which the political economy features of these questions and negotiations may be unique compared to similar decisions related to citizens. When refugee education is characterized by different political and economic considerations – mediated by possible futures in host countries – successful policies related to inclusion will require new or different ways of working than the status quo domestic education.

Our theory and the illustrative examples we draw on highlight the need to consider the contextual specifics of the political economy of refugees across sectors. The four domains of our analysis - purposes, actors and demand, incentives, and responsibility - provide a way to engage in this kind of thinking.

In applied work, we see value in mapping how these features are understood and acted upon (or not) across relevant actors and over time in host countries and among transnational actors. In particular, we expect close examination of these areas to help guide analysis of the political and economic priorities and constraints host countries face in relation to refugee inclusion; the role of global, national, and local agreements, laws, and policies in shaping accountability and the provision of rights; the design and implication of global and national governance and funding structures relevant to refugee management and inclusion; mapping stakeholders, interests, and how inclusion is conceptualized across actors vis-a-vis refugee futures and responsibility; and finally, will support analysis of potential challenges and opportunities related to sustainable financing to facilitate refugee inclusion in national systems.

As the 2023 Global Refugee Forum approaches in December and the world continues to grapple with dilemmas about how to meet the needs of a growing number of refugees in ways that are equitable, fair, sustainable, and support refugees’ goals, we hope that theories such as ours can help to support more effective solutions. Moving forward, we plan to develop usable frameworks and materials through the Refugee REACH Initiative at the Harvard Graduate School of Education to support the use of this theory as a conceptual framework in research, policy, and practice.

Please be in touch with suggestions, to share your experiences with this theory of the political economy of refugee education, or for a copy of the full article. You can reach us at reach@gse.harvard.edu.