Refugee Education and Medium of Instruction: Book Chapter

Research by Celia Reddick and Sarah Dryden-Peterson analyzes the issue of medium of instruction (MOI) for refugees through two illustrative case studies. Their findings reveal key tensions between home language instruction for literacy and learning, and inclusion of refugee learners in national school systems in host countries.

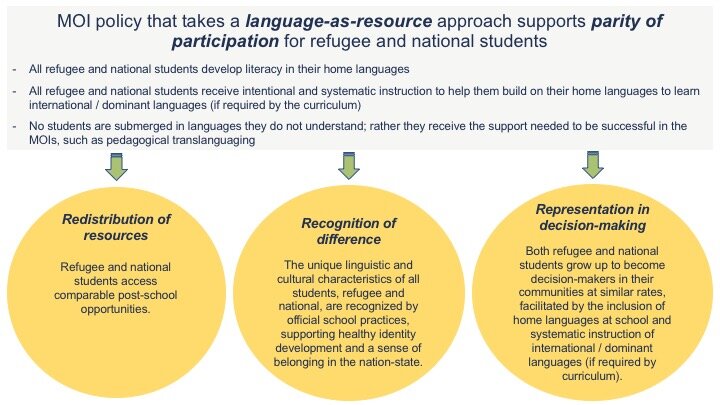

Policies and practices reflecting these two divergent bodies of research have implications for refugees’ learning, identity development, and sense of belonging. The authors also offer a framework for conceptualizing socially just policies and practices for refugees in national school systems.

Key Takeaways

We offer the following practical steps and actions based on this research below (click to expand).

+ For Policymakers

| INSIGHTS | ACTIONS | |

|---|---|---|

| The many languages that are spoken in schools and communities hosting refugees can be viewed as ‘resources’ and can support meeting global commitments to quality education. | ➟ | Conduct language mapping to determine the home languages that are represented within schools. A planning grid is also useful to determine what linguistic skills and resources might be represented among teachers, parents, and school leaders that could support learning within a multilingual educational environment. Once identified, integrate speakers of various home languages (i.e., parents, community members, older students) into classrooms as teachers and facilitators. |

| Refugee students need to be able to integrate socially and academically into host country schools and communities. To do so, they also need to develop skills in the home languages of the host country community, as well as in the international language used in the upper levels of school, both of which are important for future opportunities. | ➟ | Provide refugee students with access to additional language supports and intentional instruction, rather than a ‘submersion’ approach, in order to develop multilingual literacy that supports integration and school success. |

| Early literacy skills are best taught in the home language, with children later transferring those skills to other languages. | ➟ | Enact socially just language policies that allow refugee students to maintain languages from their country of origin in order to develop and hone their literacy skills, and so as to not lose their connections to family or community. |

+ For Educators

| INSIGHTS | ACTIONS | |

|---|---|---|

| Teaching children early literacy skills in their home language can promote better linguistic and academic outcomes later on. It can also facilitate on-going connections to home and community that are essential for identity development. | ➟ | Implement classroom language practices that allow refugee students to maintain languages from their country of origin in order to develop and hone their literacy skills. For example, organize some small group discussions about language and ensure access to classroom materials that affirm students’ diverse linguistic backgrounds and support language development. |

| Instructional practices that help students maintain home languages and proficiency in an international language, in cases where these are distinct, are conducive to academic success and students’ well-being. | ➟ | Integrate multilingual language practices in classrooms to support students’ learning and engagement, including through ‘translanguaging’. For example, use texts written in an international language and prompt student engagement in the home language, or encourage students to work together in groups using home languages to decipher course material in an international language. |

+ For Researchers

| FURTHER RESEARCH IS NEEDED TO EXAMINE: | ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

Citation (APA): Reddick, C., & Dryden-Peterson, S. (2021). Refugee education and medium of instruction. In C. Benson & K. Kosonen (Eds.), Language issues in comparative education II: Policy and practice in multilingual education based on non-dominant languages (pp. 208-233). Brill Sense.