Data to Overcome Disaster

By Anant Pai, Gladis De Leon, Eloy Bermejo, and Gonzalo Peña. Photos courtesy of authors.

Lea la versión en español aquí.

01 September 2020

Jessica Reynoso, a graduating student in the Class of 2020, reminisced in her senior speech that, “Little by little, Liceo Científico enveloped us, stretching into our daily lives, our nights, even our weekends.” As in many places, in the Dominican Republic (DR), schools support more than just classroom instruction—they create community for students, encourage personal development and reflection, and serve as bridges to the world outside of a particular community. What happens when these supports disappear? The story of Jessica’s school, Liceo Científico Dr. Miguel Canela Lázaro (LC), a public test school in the DR, demonstrates some ways that schools can continue to support communities during disaster, including through distributing humanitarian resources to families in need.

The Dominican Republic and Liceo Científico

The DR education system consistently ranks among the weakest in the world on measures of teacher certification, curriculum, and, in particular, missed class time. The average student in the DR loses 18 days of instruction due to last-minute school closures and frequent teacher strikes (not including personal absences). LC was born out of a desire to change this reality. It is among the nation’s only STEAM public schools and an example of a public-private partnership (PPP), overseen jointly by the local school board and a group of individuals.

As researchers and teachers, we were commissioned by the school’s board to undertake a project that analyzed the efficacy of this form of PPP as a replicable model, collect and analyze data, and ultimately report our findings to local, state, and national education authorities. While this study began before the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic were being felt in the DR, the data we collected was a productive resource in the school’s pandemic response.

The school is located in a rural, inland province called Hermanas Mirábal, one of the smallest in the nation, but has consistently been ranked among the top five public schools in the nation. In the 2018-2019 school year, LC did not miss a single day of scheduled programming.

Responding to the Covid-19 Pandemic

In March of 2020, school closures occurred as a result of a presidential mandate in response to Covid-19. It happened abruptly, with educational institutions given less than 48 hours to prepare and communicate with parents. The Ministry of Education offered little guidance, and other schools in the nation shut down all learning, with end-of-the-year exams looming and many questions unanswered. Committed to its mission of reducing missed class time, LC promptly announced the start of distance learning. The decision was unprecedented: Within a week, a block schedule was created, lessons were posted on the school website, and students met virtually through Google Meet.

Data as a Tool in Responding Effectively to Disaster

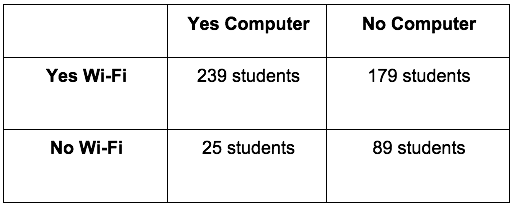

The school’s rapid response was enabled only by foundational work that gave administrators key information as they weighed options. Earlier in the year, the governing board of the school had commissioned a research project designed to understand students’ home lives. The project involved an in-person visit to each of the 532 students’ homes and survey of families. The survey included questions about guardians’ educational attainment and employment, characteristics of the household, and availability of technological devices. These data proved fundamental in the crafting of a coherent Covid-19 response, as they allowed administrators to identify gaps in resources (see Table 1).

Table 1: Data about students’ technological devices gave administrators crucial information.

Source: Oficina Técnica Provincial (Abril 2020) Análisis de las Situaciones Socioeconómico de las Familias del Liceo Científico 2019 - 2020. Provincia Hermanas Mirabal.

By the end of the week, administrators were able to contact all students who lacked Internet connection or a virtual learning device and, in conjunction with the local government and private sector partnerships, sourced Wi-Fi hotspots and tablets for all of these students. Additionally, when the government shared health and wellness resources with the school, administrators were easily able to identify students in vulnerable situations and ensure that supplies were distributed to those with the greatest need. For example, in addition to educational resources, LC distributed government meals to families facing food insecurity.

A student completes her distance learning work using a school-given tablet. Photo: Liceo Científico Dr. Miguel Canela Lázaro.

Virtual Learning May Exacerbate Inequities

While LC was quick to implement virtual learning and to prioritize equal access, preliminary data from the period of distance learning indicates that learning gaps between students widened—grades from students of higher socioeconomic status (SES) backgrounds were higher than those of lower SES backgrounds. This trend was especially strong for STEAM subjects. While further study will be required to understand the drivers of this trend, careful thought must be given to how we may reduce these inequities. Closing the technological gap is not enough to close learning gaps.

Our Lessons

Liceo Científico’s rapid response to Covid-19 highlights the importance of demographic data and communication infrastructures in a school’s capacity to respond quickly to emergencies. In Hermanas Mirabal, Liceo Científico is so much more than a school: it is a community institution that creates province-wide programming; it is a nexus of cultures and ideas where students are pushed to learn and grow; and for students, it is, importantly, a family to fall back on when things aren’t going right. Having access to crucial data allows schools to continue to play these roles: students can continue education, and families can seek and find support. The ability of administrators to maintain contact with and support families experiencing attenuating circumstances also suggests that relationships with and information about families may make schools a viable pathway for humanitarian aid distribution and continuing support for students and communities.

Disclaimer: The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this publication belong solely to the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of REACH or the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

About the authors:

Anant Pai received his B.A. in Applied Mathematics and Sociology from Harvard College (‘19). He spent the 2019-2020 academic year as a Princeton in Latin America Fellow working at Liceo Científico Dr. Miguel Canela Lázaro in the Dominican Republic. (LinkedIn | Twitter)

Gladis María de León is a Dominican Republic native who received her master’s degree in psychology in Milan, Italy. She works as a researcher for Oficina Técnica Provincial in the Dominican Republic.

Eloy Bermejo received his doctorate in Art History from the University of Zaragoza in Spain and in History and Representation of Architecture from the University of Palermo in Italy. He is the coordinator of the lower school for Liceo Científico Dr. Miguel Canela Lázaro. (LinkedIn | Twitter)

Gonzalo Peña received his doctorate in Communication from the Complutense University of Madrid in Spain. He teaches 7th grade literature in Liceo Científico’s lower secondary school. (Twitter)